“Jazz Improvisation: A Pocket Guide” is a compact, 3″x 5″ book by Dan Haerle designed to be a convenient resource for the gigging musician. As Dan Haerle says in his introduction:

This book is intended to be put into a pocket, backpack, or instrument case and carried around with you for quick reference anytime it is needed. There are many ways to use the book for daily practice and study, or as a quick reference. You do not need to go through it in any particular order. Untill all of the information you need as a player is learned, it’s all readily available in this book. Use the book as a dictionary to look up some scale or chord that you are less familiar with. Use the appendixes for daily practice since it is easy to have the book with you anywhere you may be. Good luck as you strive to be a better player!

For me, it provided just that.

Little Shop Of “to my Horror”

These past two weekends, I have been part of the band in a local high school’s production of “Little Shop Of Horrors.” I had stopped by the high school to pick up my score when they finally got them in, a few days before the first show. So, I took home the handwritten score and rehearsed the tunes for the show. Having previously done a few musical theatre gigs, I knew the music would be tricky at best.

I get to the school, and I’m told “oh, that’s the wrong score. The right ones came in today. They’re in a little bit different keys, the ones the kids have been practicing with.” Well, that’s just swell. But, it’ll be fine, just different keys… Right? Wrong. To my horror (pun slightly intended), it was totally different. Luckily, this one wasn’t hand written, and was far easier to read. But still, different.

This score had far more, and far more complex chords. Now, being the novice jazz player that I am, I don’t use extensively altered chords all that often. This musical, of course, had all the altered chords you could think of. Why? Because it’s musical theatre, that’s why. Anyway, I was fortunate enough to have this little book in my bag. While the children on stage were yelling into their headsets to see how much they could make them feed back, I was hurriedly looking up chords and was making notes in my score. Close one…

But Wait, There’s More!

Chords, chord voicing, and chord progressions are only a small part of this petite paperback. It also features functions of different scales, the II-V-I progression, guide tone paths as well as major, minor, blues, and bebop scales.

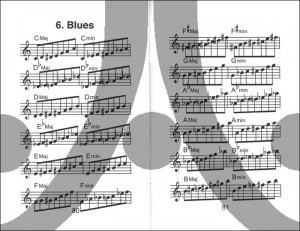

Here above you have the blues scale in all 12 keys, major and minor.

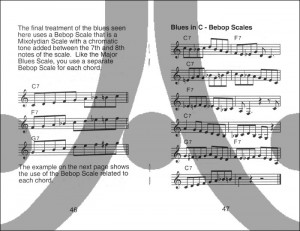

Bebop scale in “C.”

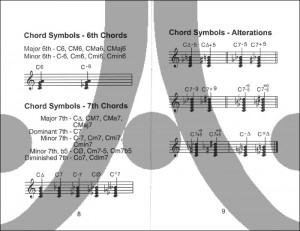

6th and 7th chord variations, and suggestions on how to use them.

On The Road Again

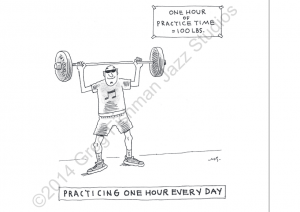

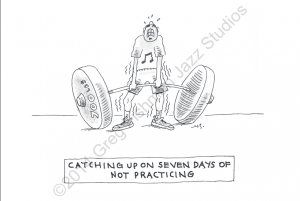

For those of you who are either gigging or traveling musicians, or just someone who doesn’t like to clutter their shelves with lots of books, “Jazz Improvisation: A Pocket Guide” is an ideal book to own. You can use to look up concepts you are less familiar with, as I did before the musical. You can use it practice scales, runs, and licks that you want to brush up on, and even create practice routines on the go. Let’s face it, we all have things we need to work on, but who wants to drag their music theory book around with them to every gig?

You know, just in case…

So go ahead and do yourself a favor, and pick up a copy of “Jazz Improvisation.” You’re lower back will notice a difference, for sure. Aebersold Jazz also offers a whole series of “Pocket” books. For whatever else you need, there might be a pocket book for it?