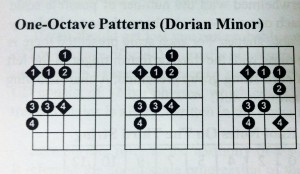

I’ve been practicing with the first set of exercises in Volume 1 for Guitar, and I’m feeling pretty good about them. I’ve been using the Dorian Minor scale shapes to improvise with the play-a-long tracks, and it’s sounding alright, if I do say so myself. But on page 42, we move into a scale that not only has an added note (8 rather than the standard 7), but is supposed to be played on certain beats to acquire the “jazzy” sound. Here we go…

The Bebop Scale

I’m not going to lie, I’ve never used the bebop scale before… And that made me a little nervous. The bebop scale only adds one note to the four most used scales, the major, dominant 7th, minor, and half-diminished. To get the desired uplifting jazz sound we are looking for, the added scale tone must always land on the upbeat. For each of these scales, a different note is added (for Major, you add a #5, for Dominant 7th, you add a natural 7th, and so on). Many of these scales contain the same combination of notes, and can therefore be used interchangeably, G7=Dm=B Half Diminished. Because it wasn’t already complicated enough.

For myself, the bebop scale is not intuitive. I’ve got to really think about what I’m doing to fit it into my music. But, perhaps that’s why it became such an iconic sound in jazz music? This whole section of the book, while only three pages, is packed with information on this scale, and how much it’s influenced the sound of jazz music.

Make friends with scales, especially the bebop scale. It’s the “glue” of the jazz language. Don’t leave home without it!

Maybe the next book I should look at is “Bebop Scales?” *Insert shameless plug here*

Ear Training

Following directly after the uniquely sounding bebop scale is a section of helpful hints on page 45 how to train your ears. One of the greatest traditions in jazz music is playing by ear. In fact, jazz music being written down in a book is a fairly recent development. Early jazzers had no choice but to learn by hearing the music. Now, some might tell you that a “good ear” is something you’re born with. It cannot be learned. Thankfully for me, that is not the case.

There is a reason ear training is required by every university music program that I know of. Just like anything else in music, it can be learned and developed, and should be. Let me clarify, by no means do I have a fantastic natural ear for picking out a tune. However, through quite a lot of practice, I learned, and I got better. It’s still something I work on to this day, but I have seen enormous progress. A little back story to help.

I come from completely non-musical stock, absolutely no natural talent in the realm of music. In fact, my dad’s toneless whistling is something of a joke among my siblings, my mom, and I. My brothers and me (who respectively play drums and keyboard) did not grow up around performing musicians, bands, instruments, live music, or anything of the like. But one day, my older brother Thomas decided he wanted to learn to play keyboard (just like his favorite artist, Sir Elton John), and Sam, my younger brother, and I jumped right off the musical cliff with him. We all started learning music together. If only we’d had a fourth brother, we needed a bass player!

About three years ago, I sat down in my first ever college course, “Sight Singing and Aural Training.” Probably not the best choice for my first class, but I didn’t know any better. To say I learned a lot would be a tad of an understatement. While this is a good place to start, listening to real players, and figuring out how they do what they do has helped me more than anything. My point in giving this little abridged history is this; if I can learn to train my ears, just about anybody can.

In music, your ears are your best friend. The sound comes into your ears and your mind processes the music. Well-trained ears can be had by everyone if they take the time to develop them.

The Pentatonic Scale And Its Use

Ah yes, the pentatonic scale. Now that your brain is sufficiently wrung from thinking about the bebop scale and training your ears, we can move on to something a little simpler. This is probably the first scale that many guitarists (if not all musicians) learn. For those who don’t know, the word “penta” originates from the Greek word “pente”, meaning “five.” As you may have guessed, the pentatonic scale consists of five tones. Because of its simplified nature, the pentatonic scale can be widely used in many genres of music without much adaption. Especially popular amongst blues players, a pentatonic scale based on the “I” of a I/IV/V progression will work fantastically well. You can play a major or minor pentatonic scale, and so it can be used over major or minor chord progressions, not to mention Dominant 7th, Half Diminished, Diminished, and Whole Tone scales.

People use the pentatonic scale more during a blues progression than in any other harmonic sequence in jazz- especially young players. There are books on the market which advocate using the pentatonic scale as a means to solo on the blues progression. The pentatonic scale should be thought of as a small part of the overall musical spectrum.

The tracks that we first used to practice our Dorian Minor scale can also be used to practice the bebop and pentatonic scales, and improvise with them in various keys. I’ve got some new things to work on! I’m just scratching the surface (not to mention my head!). Please check back for more updates as I work through Volume 1 for Jazz Guitar

One…two… a one, two, three, four!