50 years ago jazz education was practically unknown. Jazz musicians were often reluctant to pass on or giveout information on how they were able to play the way they did. I think some were afraid if they verbalized theirplaying, they might dilute their font of inspiration or lose a part of their musical self. Words just weren’t the propermedium to convey one’s musical wellspring. “Can’t you HEAR what I’m playing? Why do you want me to talk when the music best speaks my musical thoughts and intentions?

When I was a teenager, I had many questions about how the famous and not so famous musicians could playthe way they did but I had no one to ask questions of. I listened to the records over and over and here and there an answer would appear but the answers came too slowly to suit me.

I was raised in a musical family. My mother player piano and sang but not professionally and my father playedpiano and banjo. My two brothers took music lessons and played in school bands when they were young. I startedpiano lessons at age 5 and was fired by my teacher at age 10. She said, “you’ll never be a musician, you don’twant to practice, go on home!” I immediately made the natural switch to tenor banjo, which my father played. Itook lessons on banjo and played it for several years. At age 12, I began to experiment with my older brothersalto saxophone. I joined the band in the 6th grade on sax but thought it was pretty boring. In general, my schoolband experience was fun but I never felt I learned much because everything we played was so easy and boring.I wanted to be challenged.

Around the age of 14, I was reading Down Beat magazine and came across the sentence “jazz is the comingthing.” I thought to myself, “if jazz is the coming thing, I’d better get with it.” The next day I went down to therecord store and bought my first jazz records. Those were 78’s of Duke Ellington’s big band and some smallerjazz groups with people like Kid Ory and Louis Armstrong. The song, Bugle Call Rag was one of my early favorites that I played over and over.

My first real jazz teacher was records and radio listening. My second jazz teacher in real-life form was David Baker who was teaching at his home in Indianapolis, Indiana. David explained chord/scale relationships in a way

that opened up my ears and my playing received new possibilities. He offered a logical reason to know those scales and arpeggios …if I had control over them, I could better express myself and I would sound more like my heroes I listened to on records. Practicing the basics suddenly made good sense …and it would help me make music-my music!

I was probably 20 years old when I had my first lesson with Baker. From that day on, I thought in terms of “what scale goes with that chord symbol?” What is the correct or first choice arpeggio or chord.? This way of thinking quickly lead to solos that contained better note choices and overall phrase construction and this quickly led to the understanding and exploration of altered tones, blue notes, chromaticism, etc. A whole new world of musical possibilities was opening up to my ears, fingers and mind.

I began teaching privately in 1961. I taught beginning woodwinds-sax, clarinet and flute at a store in Seymour, Indiana on Saturdays. I quickly learned that I needed to sharpen my ears because I was too slow in hearing exactly what wrong notes the students might play. I needed to be able to instantly identify their mistakes and then offer the solution. This is when I began ear training in earnest.

In Seymour, at the music store, I discovered these teenagers from this small farm community in the Midwest could IMPROVISE! I found their natural ears were excellent, just untrained. None had listened to jazz but they all could instantly make melodies and phrase properly over simple scales while I accompanied them on piano. They could correct themselves when they would hit a strange note. I felt they were actually playing the rhythm and note choices their mind was hearing. To me, this was a revelation because I thought in order to improvise you had to have a stack of jazz records, drink a lot of coffee and never be satisfied with your own playing. These kids taught me a valuable lesson: Everyone can Hear and everyone can Improvise.

This is a basic premise I’ve kept in mind my entire teaching career. I see and hear the hope and promise of solos being played for money and for pleasure; for fun and as work; by pros and beginners, at home or in the concert hall; by young and old; with or without a rhythm section; for a huge crowd or for no-one but the pictures on the walls; lots of notes or not so many notes; by the educated and the uneducated; with or without government funding; on expensive instruments and on instruments falling apart. MUSIC DOESN’T CARE WHO PLAYS IT. People have a need to be creative and jazz offers us a natural outlet. Creativity is where the fun is.

Around 1964 I was asked to help teach at a big band camp called The National Stage Band Camps. I rehearsed four big band sax sections each day. Some famous jazz musicians were on the faculty: Oliver Nelson, Ron Carter, Charlie Mariano, John LaPorta, Marian McPartland and others. I enjoyed teaching there for several weeks each summer but I felt something was missing: ‘The teaching of Jazz – Improvisation!’

Anyone could learn to read a big band chart but I felt sorry for all those kids who never got to stand up and take a solo. All they did was read music, play their part, follow the leader. After a year or two of teaching at the summer camps, I made the suggestion of making a combo of some of the better students and rehearse them before dinner each night. This quickly led to a ‘listening class’, which would meet after dinner. I recall one faculty member cussing me out because I was showing some sax student how to finger high ‘A’ and other notes above the normal sax range. He felt we shouldn’t show them the future until they had mastered the basics.

In 1970 or 1971 I suggested to Ken Morris, the owner of the summer camps, we form a combo workshop. This he did in 1972. We held our first combo camp in Normal, Illinois and probably had 65 students, mostly all teenagers. Our faculty consisted of approximately ten people. It was a success and we are now nearing our 32nd year of combo/improv summer workshops. The early years attracted primarily teenagers. In the eighties, we began attracting more and more adults and the trend has continued. The fact we attract so many adults convinces me that humans have a strong desire to be creative with music. Improvising is a natural way to express your emotions, intellect and your spirituality. Mankind has improvised since inhabiting our planet, so making music, sounds, and improvising seems to be very natural.

This past summer, 2003, we held two week-long combo workshops and accommodated 700 people. Half were under age 21 and half were over age 21. Things have changed dramatically over 30 years. Our faculty this year consisted of 65 teachers. We hold our combo workshops at the University of Louisville in Louisville, Kentucky near the end of June and the first week of July. www.summerjazzworkshops.com At our combo camps we have up to 55 combos all rehearsing at the same time, twice a day. The emphasis is on improvising, learning how to make your own music. It’s not mystical or only for a few. You do have to have desire and it helps to develop a passion for this music. We also offer jazz theory, ear training, and master classes on each instrument, student jam sessions and many faculty concerts. Working at the National Stage Band Camps in the mid-sixties led to my producing the first Aebersold Play-A-Long LP/book set in 1967. Incidentally, I rarely used the word improvisation back then because it just wasn’t used. People said the word ‘jazz’ although the word jazz didn’t always explain what we were doing. In time, the word jazz and the word improvising became intertwined.

I can remember taking some volume 1 Play-A-Longs to workshops and would literally sell them out of the trunk of my car. Kind of like a Gypsy salesman. I took a few to music stores in Louisville, KY to be sold on consignment. I also put a very small ad in Down Beat magazines classified ad section. We sold Volume 1 at $6.95, which included postage. I can recall saying to my wife: “wow, if we could only sell one copy a day! That would be $49 a week,” minus postage of course. One time a lady at a sub-postal station wouldn’t put postage on a package of Vol.1 I was mailing. I asked her why she wouldn’t send it and she said, “it’s JAZZ!” I didn’t know what to think …the manager appeared and took care of me and a week later that sub-postal station was out of business. To many people, jazz was a dirty word: something to be avoided; even jazz education, at times, was dirty back then. Volume 1 was a single item for several years and I really had no desire to broaden into other educational products or volumes. I assumed if Volume 1 were a good idea, the Berklee School of Jazz would put out their own series and improve on ‘Music Minus One’, which was offering some jazz Play-A-Longs at the time. MMO had some sets but I felt there wasn’t enough time or space on each track to actually solo. Clark Terry and others would solo and then leave some choruses for the student to solo. I felt there was a need to have a rhythm section background recording, which allowed as much time to practice as possible. So, when I made Volume 1, each track lasted about 4 to 5 minutes and the emphasis was on soloing, not playing a written melody from the book. Incidentally, there were no written melodies in my Vol.1 book.

In 1970 I put out Volume 2 ‘Nothin’ But Blues.’ It was a hit and I immediately sold more of Volume 1. A few years later Volume 3, ‘The II/V7/I Progression’ arrived and I wondered if anyone would use it because the title was “Greek” to most people. My classified ad in Down Beat magazine grew just a little larger. It seemed to boost sales of Volume 1 and 2. Not being a businessman, this was all very interesting to me. By 1976, nine years after inception, I was ready to put out Play-A-Longs using songs by Charlie Parker, Miles Davis and Sonny Rollins – my musical hero’s …Volume 6,7, and 8. Using musicians like Ron Carter, Kenny Barron and Rufus Reid helped legitimize the concept of using Play-A-Longs to learn jazz. By this time, many pros were using them to practice with at home and to warm up for jobs. They were becoming part of the ever-broadening musical landscape of jazz education. Now, with 107 Play-A-Long volumes, people all over the world are enjoying playing with professional musicians in their homes, classrooms and for profit as street musicians and in coffee houses. Remember, then as now, many educators thought you ‘can’t teach jazz.’ Teaching, to them was often following a ‘lesson plan’ where everything you do in the classroom is mapped out and written down in advance. My Play-A-Longs didn’t map out a lesson-plan. I assumed the teacher had a sense of adventure and exploration and would find various ways to incorporate my Play-A-Longs into their teaching. Often, this has proven to be the case. I also realize there are many who have bought the Play-A-Longs and have no idea how to utilize them. Our present education system does not show the novice teacher how to be creative in the classroom. This seems to be something you have to learn on your own. No Play-A-Long offers spoon-fed solutions to guaranteeing the next generation of jazz players. Since jazz employs invention, imagination must be used when using any type of Play-A-Long recording.

Higher education must take the lead and insist that improvisation be taught as part of formal, musical education. There is nothing to fear in incorporating improvisation into the general musical curriculum. I feel young music students who have been studying their instruments for several months are ready to be shown and encouraged to improvise with the notes they have learned. In addition to learning to read music and rhythms on the written page, they should be strongly encouraged to explore their own musical wellspring using what they have learned thus far. I heard from some music educators that improvisation shouldn’t be taught or encouraged until the student as a firm grasp of the basics and has been playing for 3 or 4 years. I don’t feel this is appropriate. When the student can play five notes, let them improvise with those five notes. Melodies don’t have to contain all the notes of a scale or chord. Let the student’s imagination blossom at each stage of their musical tutoring. I feel this is where a good teacher is extremely important in constantly encouraging creatively and use of imagination. Of course, if the teacher doesn’t improvise, what I’m suggesting is probably not going to take place and those students under his/her tutelage will not benefit from the lessons improvisation can provide. I firmly feel learning to improvise early in life can lead to playing music for ones own pleasure throughout ones’ entire life. Music is part of life and there is no valid reason to stop playing music after graduating from school just because there is no organized ensemble to play with. If you learn to improvise, you can use it as a part of the enrichment of your daily life. Walter asked me if I felt my Play-A-Longs have reached my goals. Since entering the publishing business in 1967, I’ve been interested in helping people all over the globe to realize their musical dreams. If their dream is to improvise and play music that originates in their own minds, I feel the Play-A-Longs help fulfill that need. When I began with that very first Volume 1, A New Approach to Jazz Improvisation, I never dreamt it would be the beginning of a series of book/recording sets that would influence music education all over the world and set higher standards of practice in an organized manner. The Play-A-Long idea allowed people to practice jazz in their homes, in private. They could experiment with a good rhythm section without others hearing them and thus it gave courage to young and old alike to try this music called jazz. Currently, every second of every day, someone around the world is playing music with my Play-A-Longs. Had you told me this in 1967, when I first produced Vol.1, I would have said you were crazy. I am delighted that the Play-A-Longs have brought so much happiness to thousands of people the world over.

My career as an educator, publisher and professional musician has been along the lines of jazz itself-unpredictable, improvised, spontaneous and exciting. Here are several final thoughts concerning jazz education:

Everyone can improvise.

1.

“You either have it or you don’t” is a myth and needs to be deleted from our consciousness.

2.

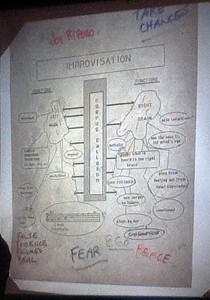

The two most prominent fears when beginning to play jazz are hitting wrong notes and getting lost.

3.

Use overhead projectors to shown your class the chord progressions, scales and chords to songs. Use

4.

the visual and the aural in teaching jazz. Chord tones (1,3,5) played on beats 1 and 3 (in 4/4 time) have always been important in Western

5.

Music. When chord tones are played often enough on these beats the listener can HEAR the intended harmony. When students get lost, point to the music and help them get back on track.

6.

Recordings are some of the best teachers.

7.

For many around the world, my free, red, Jazz Handbook is the guide to learning jazz.

8.

I’ve never thought of my Play-A-Longs as being a method. They are tools that can guide a musician to

9.

tapping his or her own originality. I doubt there will ever be a foolproof method for teaching jazz. Publications are tools. The instructor is the guide. Imagination is the source. The most important Play-A-Long sets for beginning improvisation are: Vol.1, 21, 24, 84, 3, 16, and 54.

10.

Never assume the student can’t do something you ask.

11.

The state of jazz education is fine. We need many more qualified instructors who play the music and have a passion for passing the information on to others via the classroom. The idea that you “can’t teach jazz” needs to be erased. A new mind-set needs to be inserted into higher education and that is ‘everyone can improvise.’”